Overview

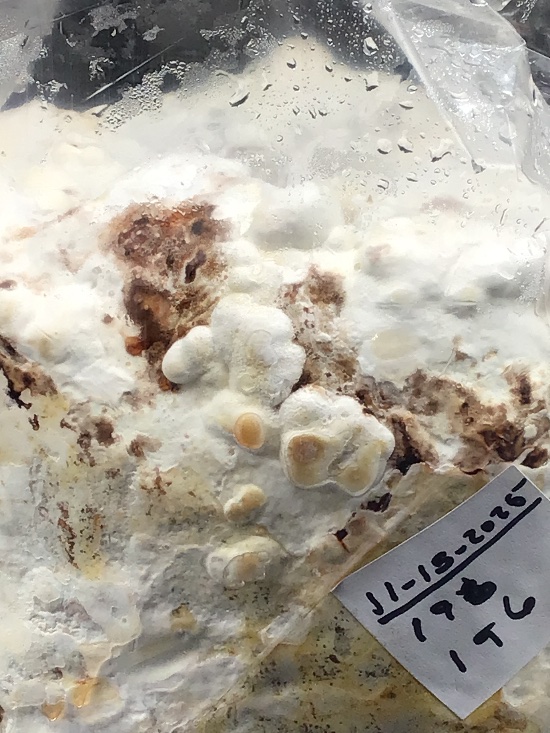

This article documents an experimental technique: allowing yeast to ferment a sugar-water–hydrated sawdust mix before sterilization, with the goal of “conditioning” the substrate and enriching it with yeast-derived nutrients.

What Happens When You Pre-Ferment Sawdust With Yeast?

Pre-fermenting hardwood sawdust with yeast is an experimental technique that leverages simple sugar fermentation to “condition” the substrate before sterilization. This process can modify the chemical and physical structure of the sawdust, potentially improving colonization speed and overall biological efficiency for species like shiitake and oyster mushrooms.

In practical terms, this kind of substrate conditioning can be logged and compared over time using tools such as the MycologyLog substrate hydration calculator and the spawn rate calculator, so you can see how fermentation variables correlate with yield and colonization times in your grow log.

1. Yeast Breakdown of Simple Carbohydrates

When yeast is added to a sugar-water–hydrated sawdust mix, it immediately begins consuming simple carbohydrates. Hardwood sawdust only contains trace amounts of natural sugars, so the added sugar in the solution becomes the primary food source for the yeast.

This metabolic activity leads to:

- Release of carbon dioxide (CO₂)

- Mild heat generation

- Production of trace vitamins, especially B-vitamins

- Production of amino acids and nucleotides

- Partial pre-digestion of the soluble fraction of the substrate

Vitamins and amino acids are largely heat-stable, so they remain in the substrate even after sterilization. This is beneficial for mushroom mycelium, which relies on B-vitamins as important metabolic co-factors during colonization and fruiting.

2. Yeast Biomass as Nutrient Enrichment

Once the fermentation phase is complete and the substrate is sterilized, the yeast cells are killed. However, their cellular components remain dispersed throughout the sawdust and act as a nutrient supplement.

Yeast cells are naturally rich in:

- β-glucans

- Ergosterol

- Amino acids

- Vitamins (B1, B2, B3, B6, folate)

- Trace minerals

- Organic nitrogen

These attributes make yeast biomass functionally similar to commercial yeast extract, which is widely used as a high-quality supplement in mushroom and microbial media. By allowing yeast to grow and then sterilizing it in the substrate, you effectively create a “poor man’s yeast extract” inside the block.

3. Mild Organic Acid Production and Fiber Softening

During active fermentation, yeast produces small amounts of organic acids. These typically include:

- Succinic acid

- Acetic acid

- Malic acid

These acids can help to:

- Slightly soften lignocellulosic fibers in the sawdust

- Improve water penetration into the substrate structure

- Increase digestibility for fungal enzymes

- Mimic natural “pre-rotting” conditions found in forest substrates

Although the acids themselves are neutralized or transformed during sterilization, the structural changes they induce in the substrate remain. The result is a sawdust matrix that is potentially easier for mushroom mycelium to colonize and digest.

4. Sterilization Preserves the Benefits

The final sterilization step kills all yeast cells and competing microbes, but it preserves the biochemical and structural changes created during fermentation. After this process, the substrate can be described as:

- Partially pre-digested

- Enriched with vitamins and micronutrients

- Supplemented with yeast-derived organic nitrogen

- Softened in terms of lignin and cellulose structure

This is conceptually similar to the composted or conditioned sawdust historically used by shiitake farmers in Japan, where partial decomposition improves substrate performance and yield potential.

What Does Research Suggest?

While this is an experimental technique, it aligns closely with published work on fermented and biologically conditioned substrates for gourmet mushrooms.

Yeast-Fermented Substrates and Mushroom Performance

Studies on Pleurotus (oyster mushrooms) and Lentinula edodes (shiitake) have shown that substrates enriched with fermented yeast biomass can:

- Increase colonization speed

- Improve biological efficiency (BE) by roughly 10–30%

- Stimulate earlier expression of lignin-degrading enzymes

- Promote more aggressive and uniform mycelial growth

In many of these trials, researchers used Saccharomyces cerevisiae, mixed cultures of lactic acid bacteria and yeast, or brewery yeast waste. A small-scale “home” fermentation of sawdust with baker’s yeast follows the same core principles, even if the exact conditions differ.

Fermentation and Shiitake Browning Time

Research and farm-level observations from Japan report that pre-fermented sawdust can reduce shiitake browning time by approximately 10–20%. Blocks often show:

- Faster transition into the browning phase

- Denser, whiter mycelial coverage

- Modest improvements in first flush yield

- More pronounced yield gains in the second flush

These effects are typically linked to:

- Softening of lignin-rich components

- An increased fraction of soluble carbohydrates

- Additional vitamins and cofactors from yeast

- A substrate structure that retains water more effectively

Potential Drawbacks and Risk Factors

Fermentation adds complexity. Used carefully it is a tool; pushed too far, it can become a contamination liability.

1. Excess Sugar and Contamination Risk

If the yeast does not fully consume the added sugar before sterilization, that residual sugar can:

- Caramelize or burn during sterilization

- Form sticky clumps inside the block

- Serve as an excellent food source for bacteria or mold once the block is opened

To reduce this risk, keep sugar additions moderate and fermentation times sufficient for visible activity without letting the substrate “over-ferment.”

2. Over-Fermentation and Unwanted Metabolites

Very long or anaerobic fermentation can generate compounds that are inhibitory to mushroom mycelium. These may include:

- Fusel alcohols

- Biogenic amines

- Butyric and other unpleasant-smelling acids

A controlled, relatively short fermentation window (for example, around 24 hours with good oxygen availability) generally stays in the “mild conditioning” zone rather than drifting into anaerobic spoilage.

3. Over-Enrichment and Trichoderma Risk

Highly enriched substrates, even when properly sterilized, can be more vulnerable to contamination at the moment fresh air is introduced for fruiting. Excess nitrogen or residual simple sugars may favor fast-growing competitors such as Trichoderma.

For this reason, most growers experimenting with fermented sawdust opt for light to moderate enrichment rather than pushing the nutrient load to maximum levels.

Conclusion

Pre-fermenting sawdust with yeast is a promising experimental method for substrate conditioning. By allowing yeast to transform added sugars into biomass, vitamins, and mild organic acids, growers may be able to create a more digestible, nutrient-enriched substrate that supports faster and more robust mycelial growth.

As with any enrichment strategy, the key is balance: modest sugar additions, controlled fermentation time, and good sterilization practices can help you capture the benefits of biological conditioning while keeping contamination risks manageable. Tracking these variables in a dedicated grow log like MycologyLog makes it easier to spot patterns over multiple batches and refine your process.